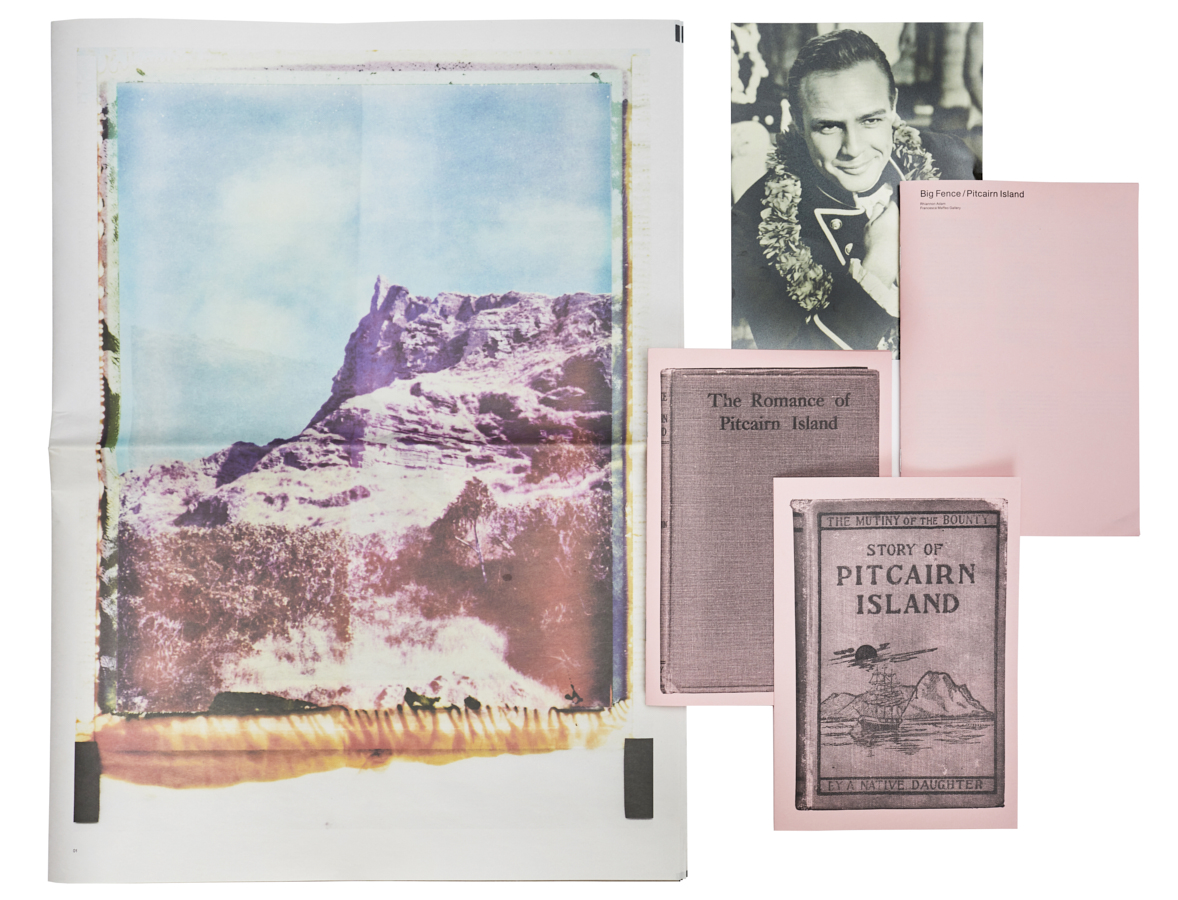

Big Fence / Pitcairn Island

Text: Gemma Padley

It is a story that endures to this day: the rising up of mutineers against Captain Bligh in 1789 and Bligh’s epic journey of survival in the Pacific. We can thank Hollywood for exploiting the haziness around what happened when Master’s Mate Fletcher Christian, and his fellow mutineers settled with a group Tahitian captives on Pitcairn Island. Certainly, the films with their heroic, dashing stars are at least partly responsible for perpetuating the romantic image of this most mysterious of islands – the last British Overseas Territory in the South Pacific.

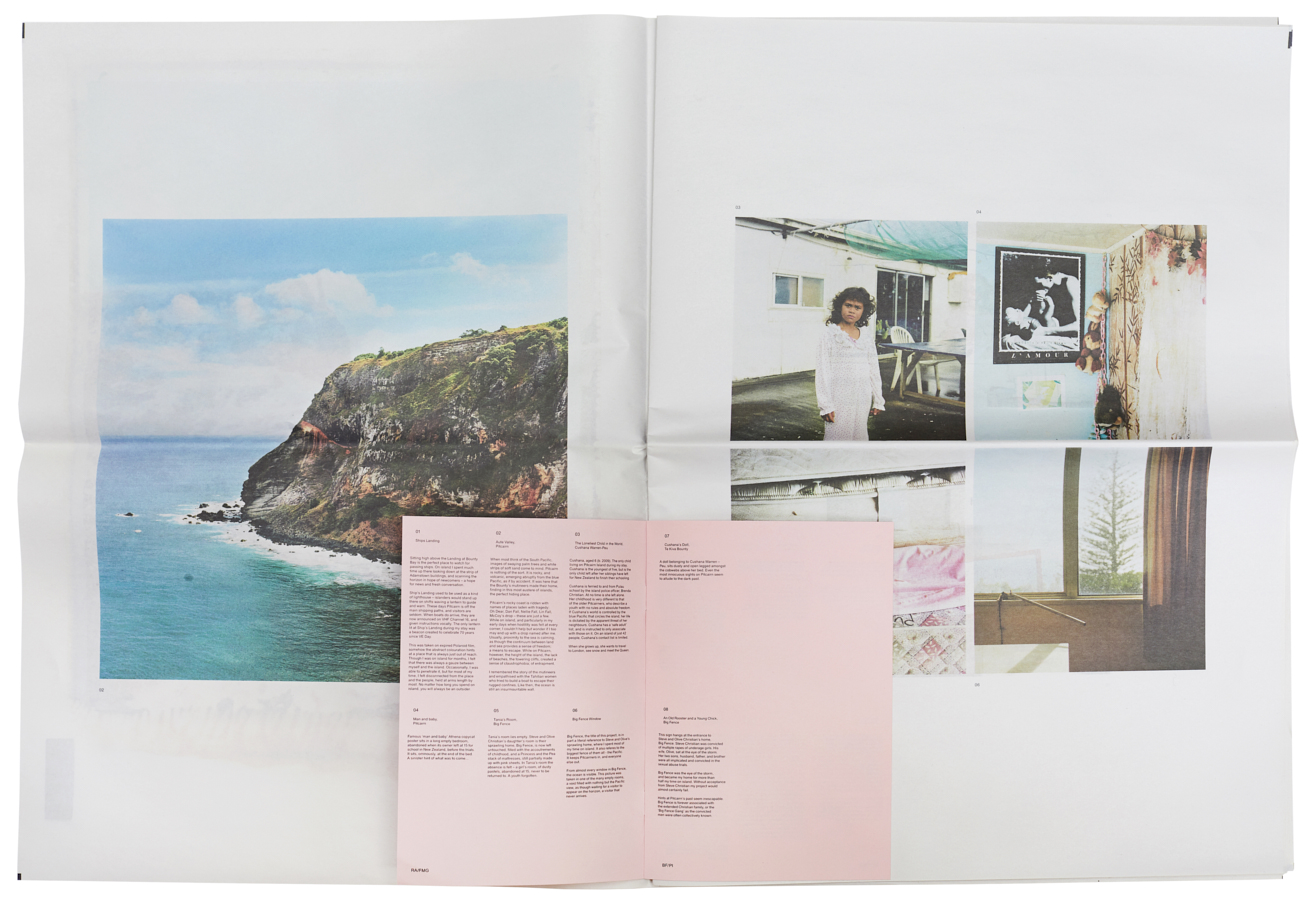

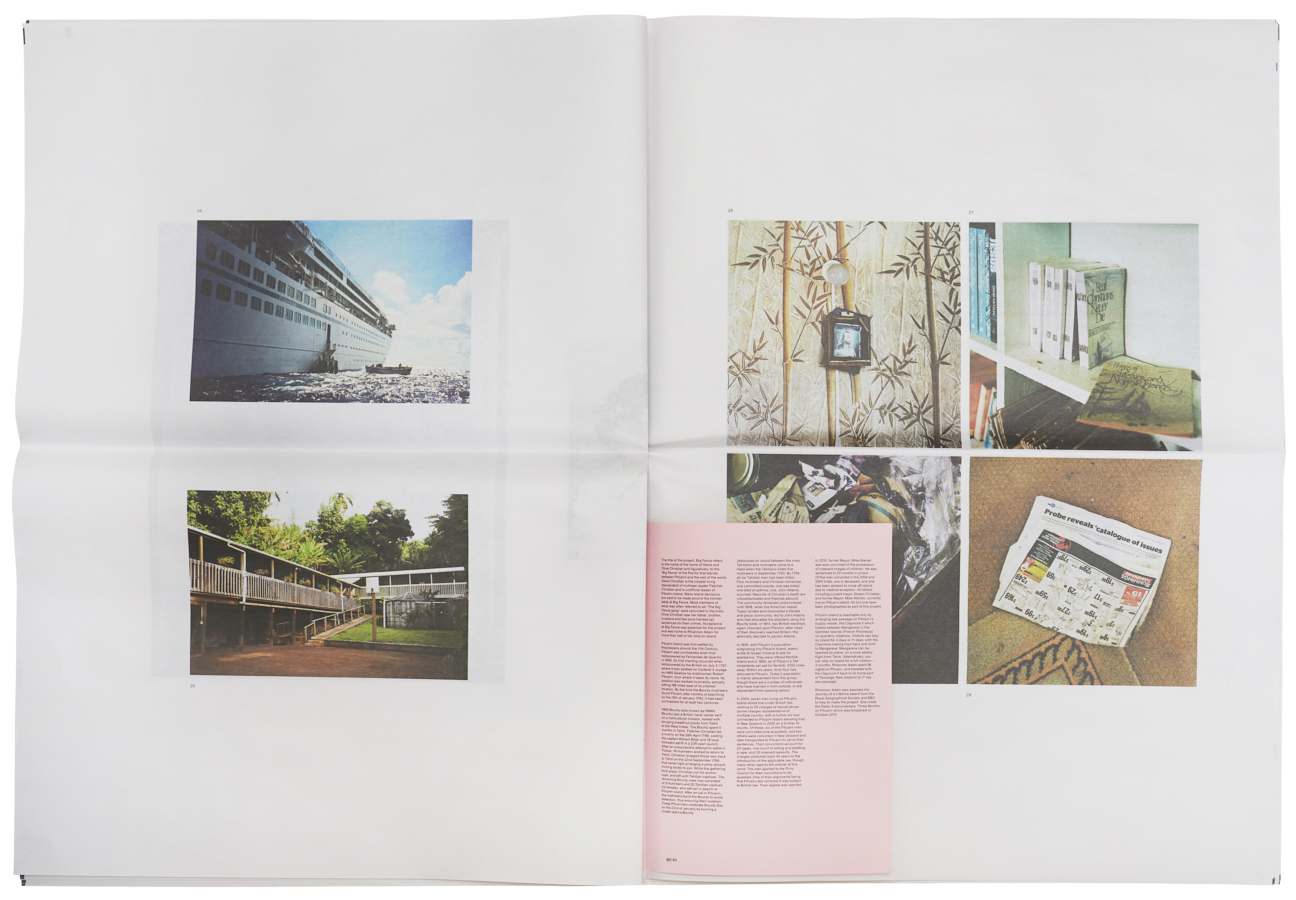

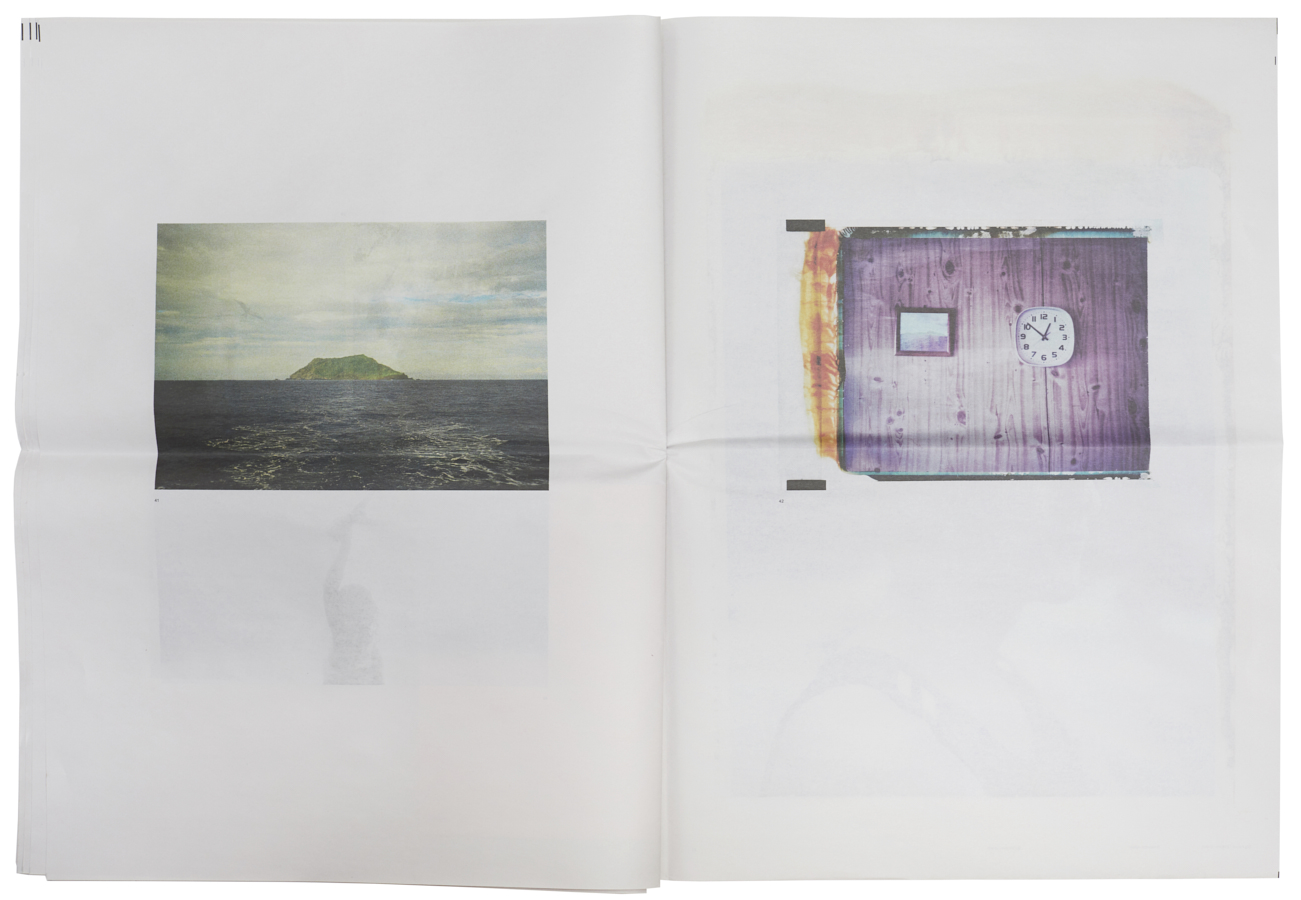

When Adam made it to Pitcairn in 2015, a long and arduous journey in itself, the reality could not have been further from the romantic visions of film and fiction. A volcanic mass with rocky shores measuring just two miles by a mile, there is no way off the island for three months at a time, until the cargo-passenger vessel returns. Cut off from the rest of the world, the inhabitants – fewer than 50, most of whom are descendants of the original mutineers – exist in a claustrophobic environment.

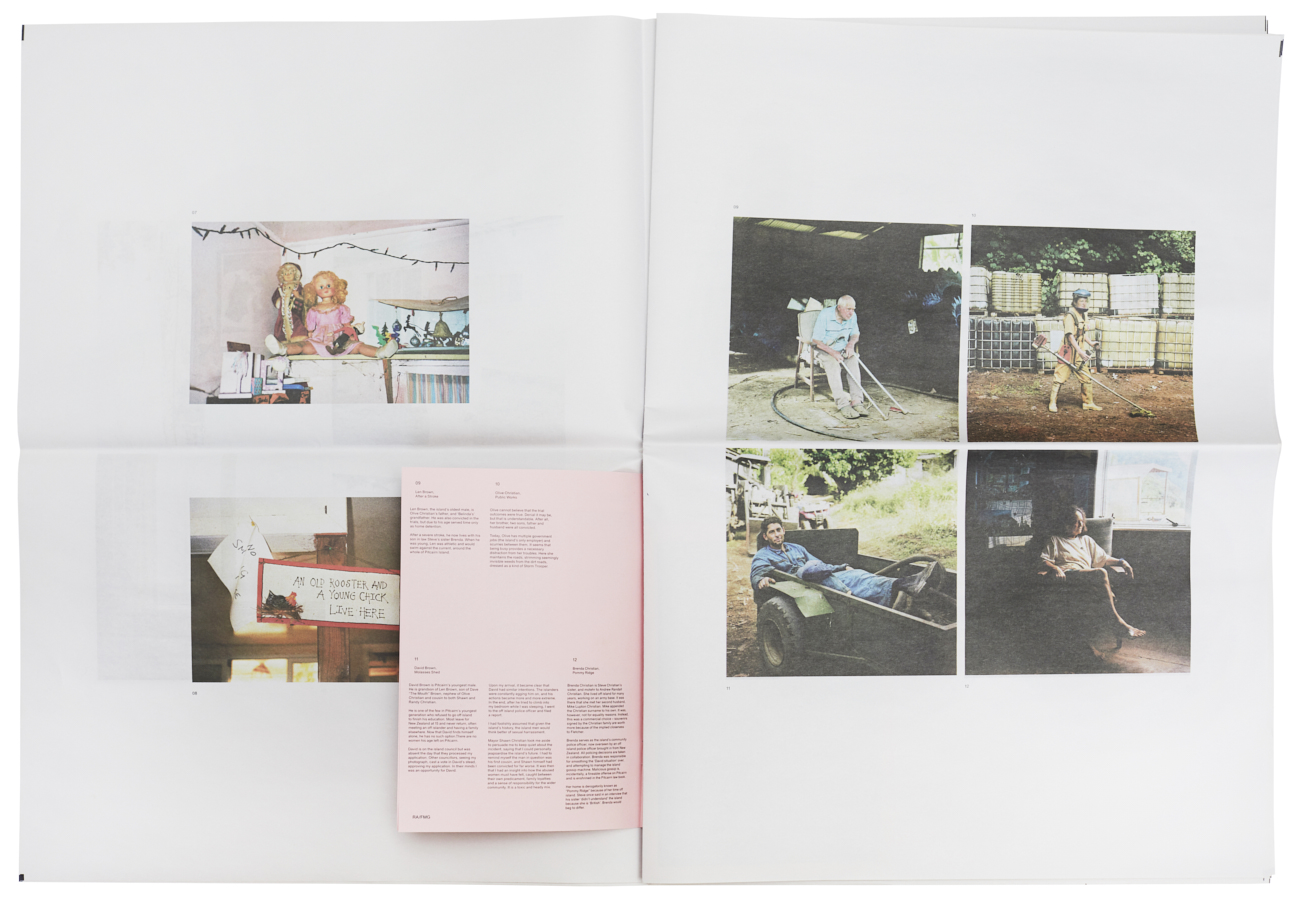

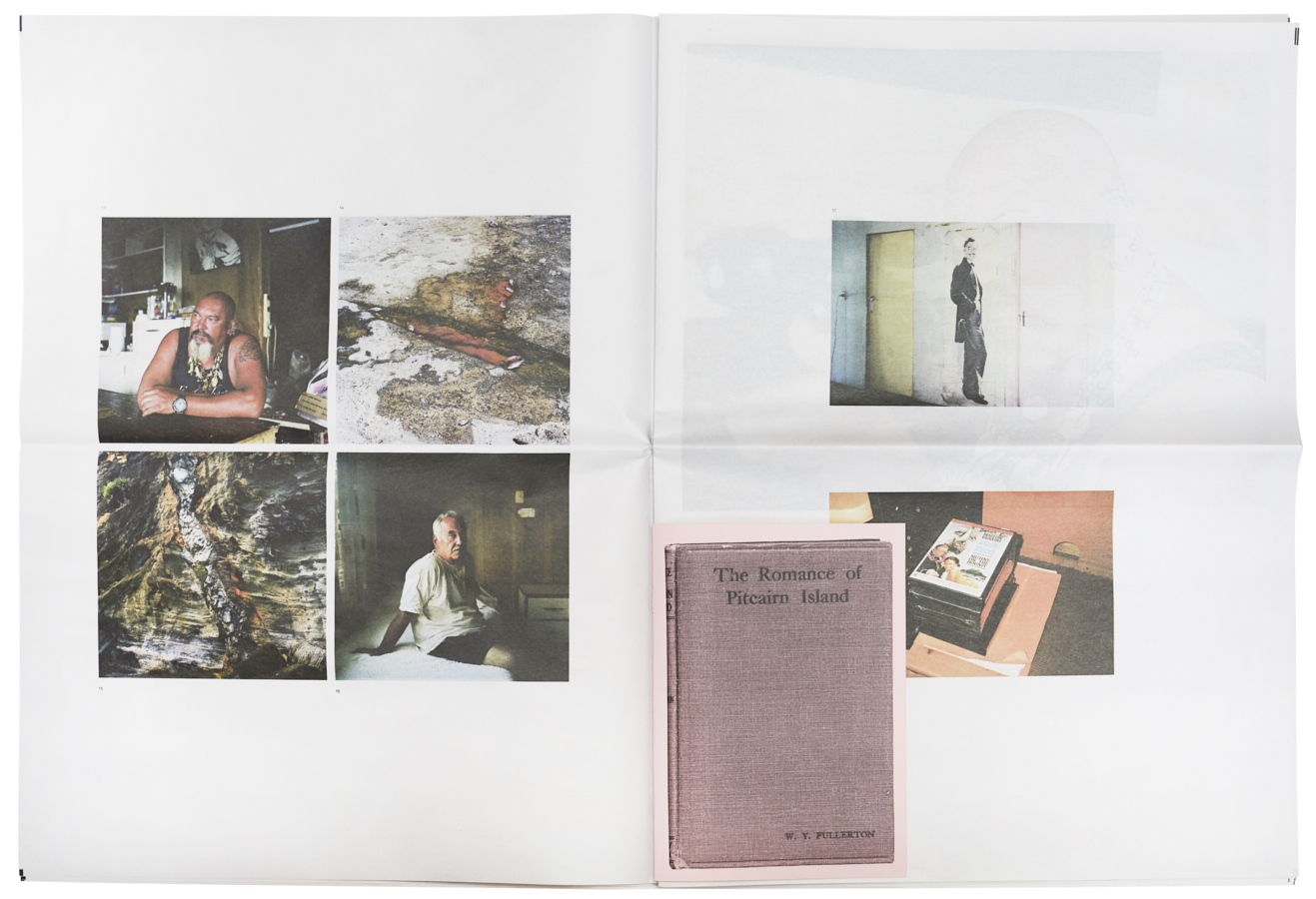

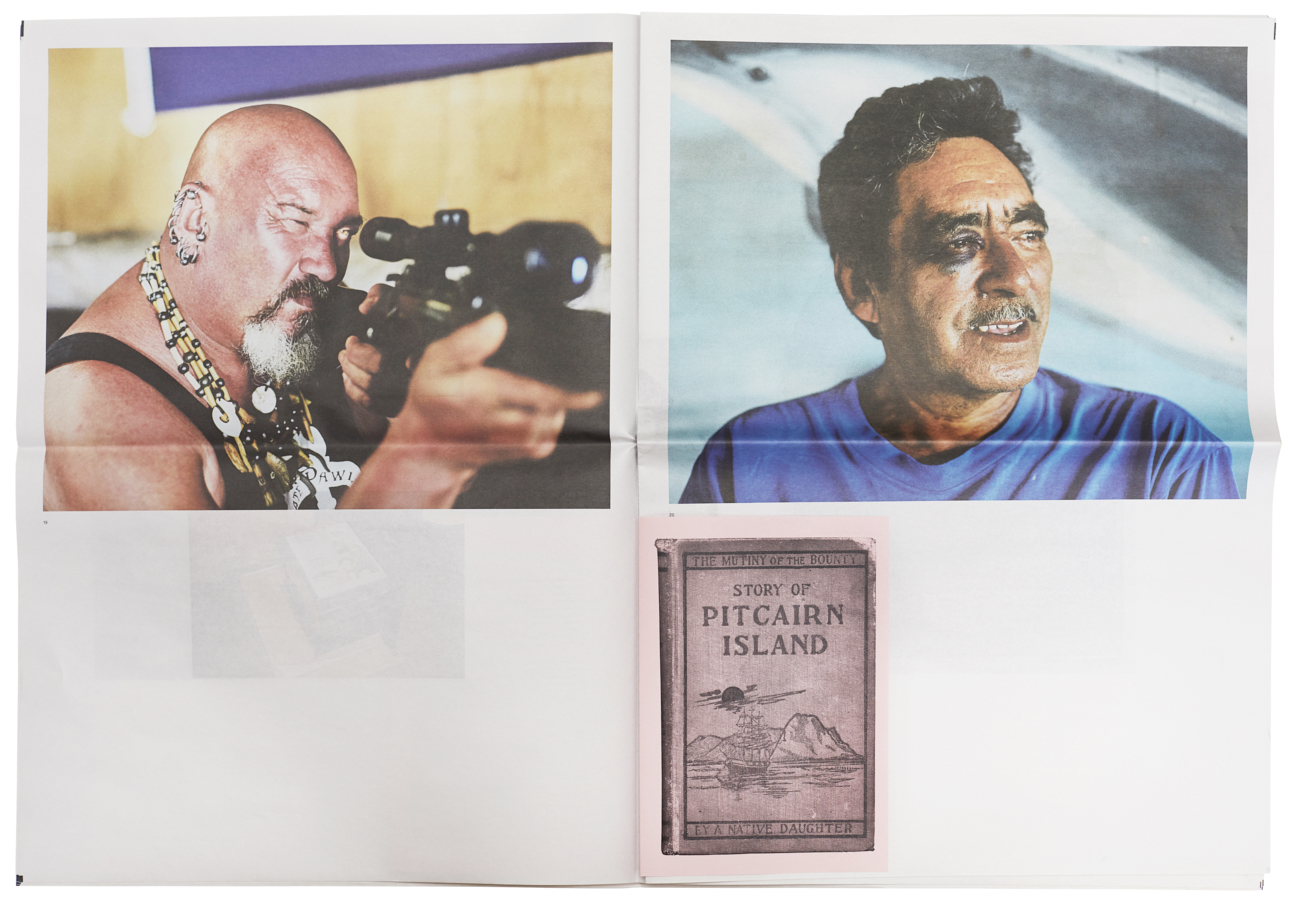

Adam’s photographs, with their voyeuristic edge and moments of intimacy masquerading as casual snapshots, or, in the case of the portraits, possessing an almost accusatory feel, are as complex and unyielding as the island itself. The exhibition is not meant to be an easy viewing experience. Where we might expect to see picturesque images of the island we are given claustrophobic interiors and stifling portraits, while the inclusion of different formats and objects – from cabinets of curiosities to audio excerpts – is a deliberate attempt to disorientate the viewer, to recreate something of the ‘discombobulating’ experience that is life on Pitcairn.

In 2004, the island became embroiled in a sexual abuse scandal from which it has never recovered. Eight men were convicted of sexual crimes, many against young girls. The convicted men served time for their crimes at HMP Pitcairn, and most still live on the island. Sentences were lenient, and since the people on Pitcairn have no freedom as it is, a prison sentence is little more than an abstract concept. Consequently, the past weighs heavy on the island; there is a sense of complicity in the islanders’ silence.

Although well aware of what had gone on, Adam hadn’t intended to make a project about the abuse scandal. Initially, she was interested in exploring the notion of ‘Utopia’ – how it could be understood as a construct born of need or desire. How can it be that Pitcairn is symbolic for some as a paradise, but for others a nightmarish ‘Lord of the Flies’ reality? Such is the power of the Bounty myth and indeed the mystery surrounding faraway places – rational thought becomes distorted. You can see evidence of these deep-rooted idealistic beliefs on Pitcairn: a stack of DVDs and a Clark Gable poster nod to the Bounty story, and yet the squalor in which people live is completely at odds with the idea of a tropical idyll.

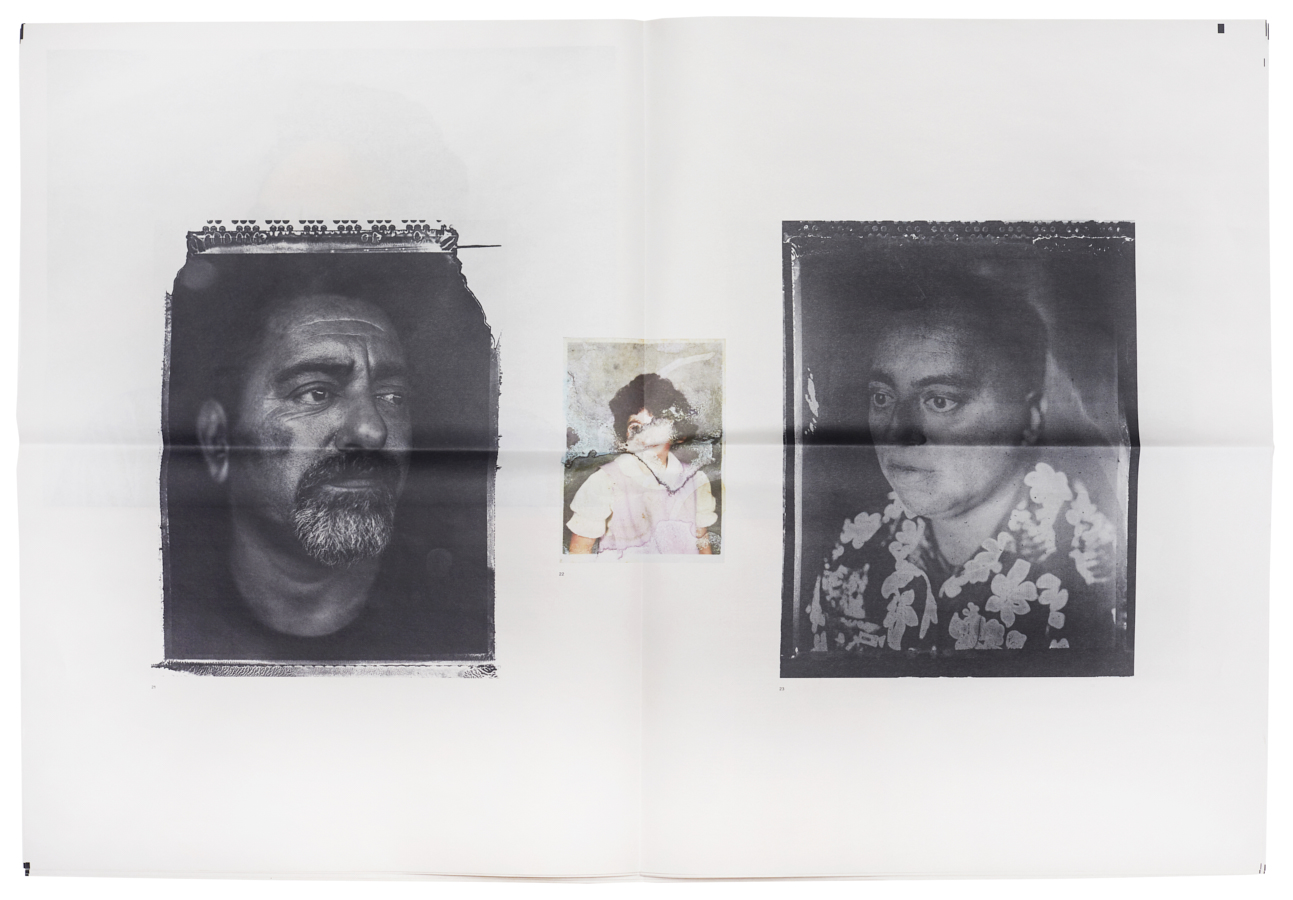

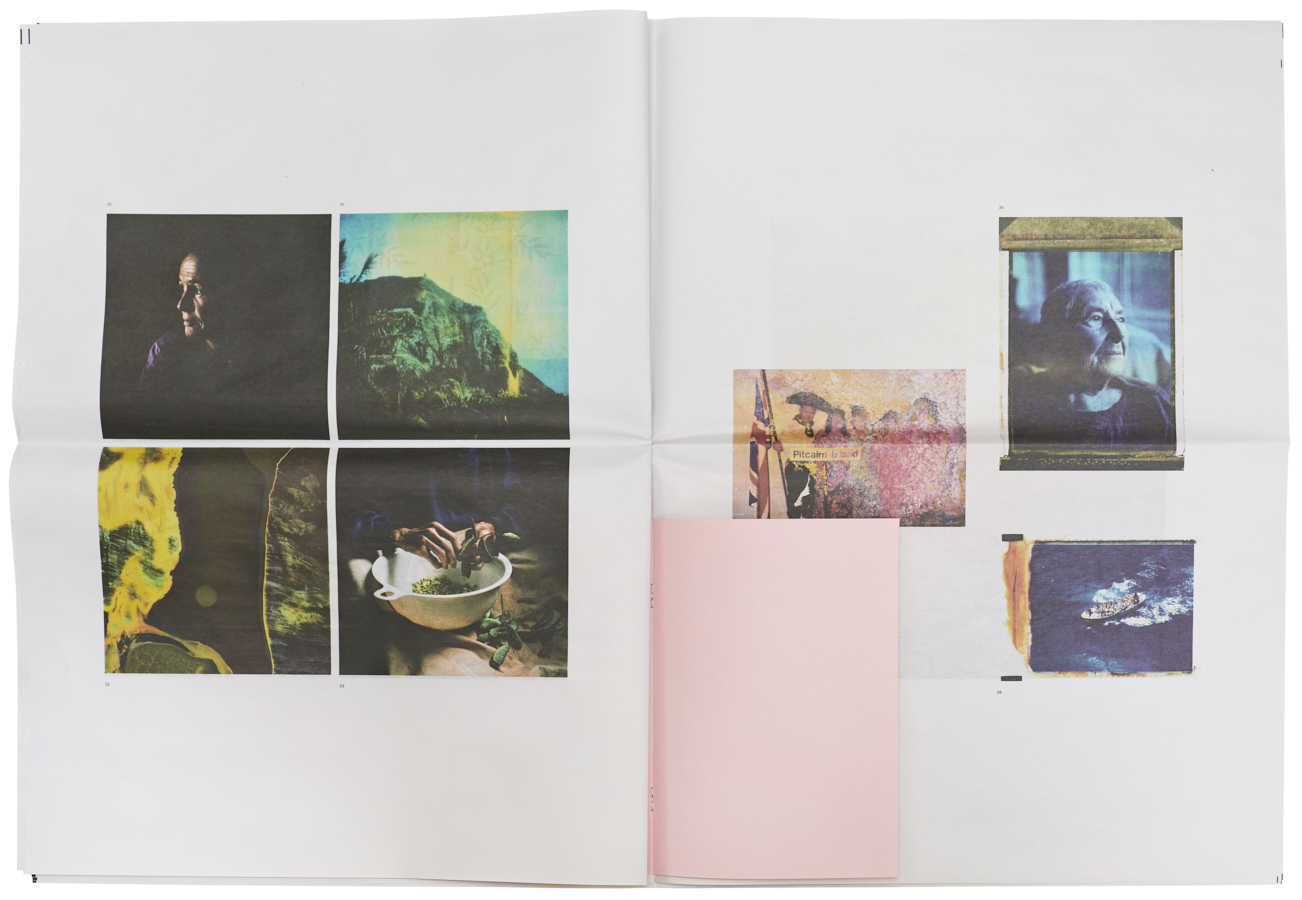

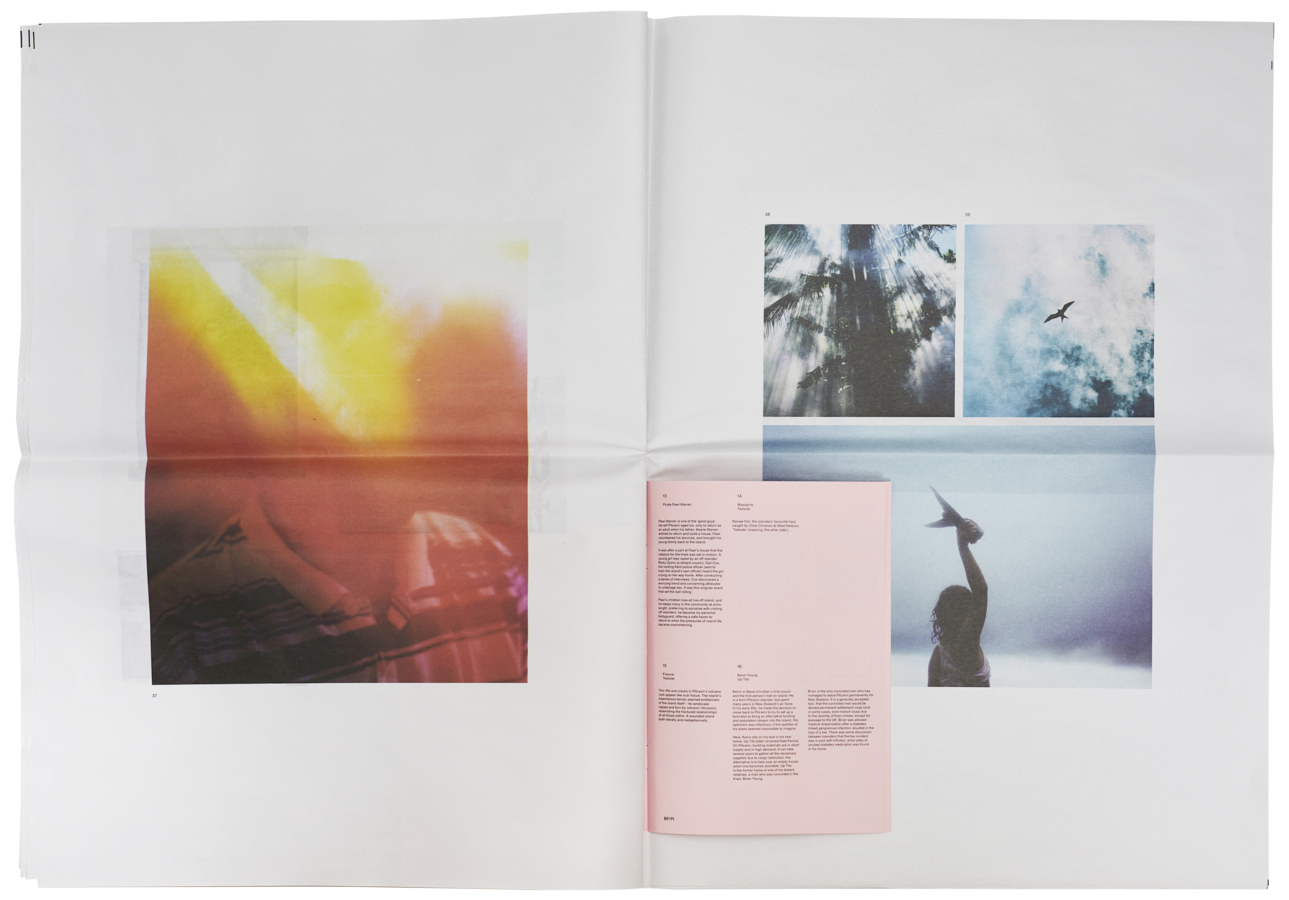

Making any photographs at all was almost impossible as the residents, wary of outsiders, were reluctant to be photographed. Consequently, most of the portraits were taken inside away from prying eyes, with each sitter pictured alone, often refusing to meet the camera’s gaze. Photographs of empty rooms evoke a sense of loss while pink tones subtly call to mind a childhood lost. Ghostly found photographs, their surfaces marred by the ravages of time and the harsh island environment, are like lost relics – reminders of a past that cannot be so easily erased.

We catch glimpses of magic and fantasy too: there is the dreamy image of a girl, her arm outstretched, and the Polaroids with their hazy appearance and soft tones and hues depicting dreamlike realities. One in particular encapsulates the sense of magical realism the island exudes. In it exotic-looking trees stretch out from the corner of the frame while a rugged mountain looms behind. At the top, a solitary tree is just discernible, the uneasy symbolism of this and the flame-like streak across the Polaroid’s surface all too apparent. If the degrading Polaroid film mirrors the fragility of the island community, the very landscape itself – with its treacherous cliff edges and steep sides – reflects the stifling atmosphere contained within.

This is not just a story about a strange, lost island, or even a deeply personal tale of one woman’s grit and determination in the face of adversity – although it is of course both of those things. It is a story that could happen to any woman – visitor or islander, child or adult, then or now; a story of what happens to human behaviour when no one is watching.